Teacher Profiles

Teachers who have expertise working with children who are deaf-blind are essential members of early intervention and educational teams.

In many states they are teachers of students who are deaf/hard of hearing, are visually impaired, or have severe/multiple disabilities. Most have had additional training or professional development in deaf-blindness. A few states have, or are working towards, a specific certification for teachers of students who are deaf-blind.

On this page you will learn about some amazing teachers—how they became interested in deaf-blindness, the type of training they’ve had, and their thoughts about and hopes for deaf-blind education. Some work in classrooms or early intervention settings. Others are itinerant teachers who provide support to numerous teams.

For more teacher profiles, see Utah Teachers of the Deaf-Blind.

Teachers Featured on This Page

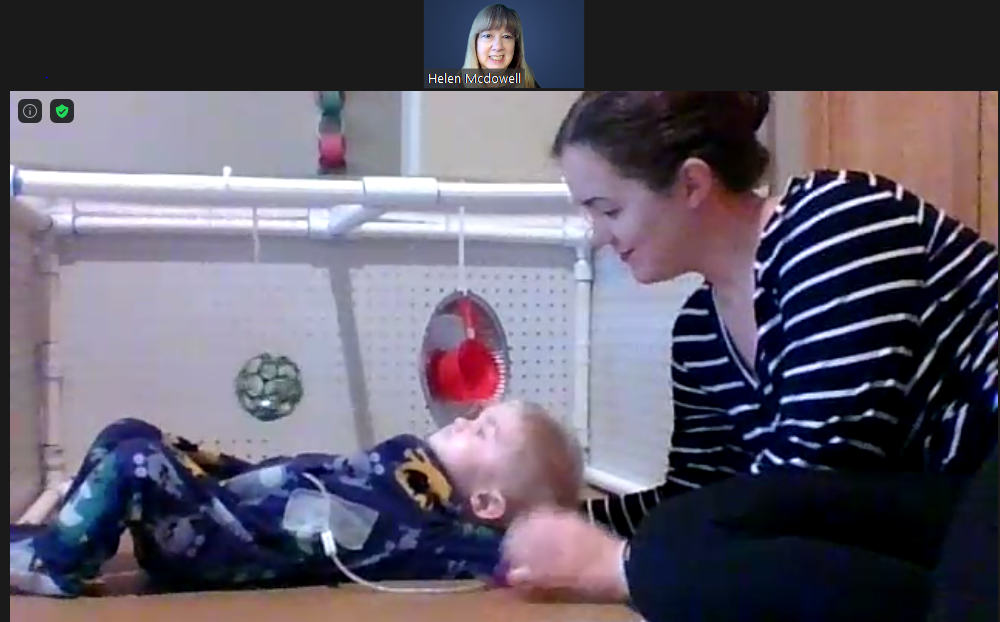

Helen McDowell - Arizona

Published January 2021

Helen McDowell, a teacher of the deaf and hard of hearing, works for the Arizona State Schools for the Deaf and the Blind Early Learning Program. Helen first learned about deafblindness in 1986 during her graduate program at San Diego State University and became more involved in 1995 when she had a new student with deafblindness who had intensive support needs. At that time, she contacted the Arizona DeafBlind Project for assistance. She attended a summer workshop and in-depth training events offered by the project, and eventually became a regional consulting teacher for students with deaf-blindness.

Helen currently works with a 9-month-old who has profound bilateral hearing loss and congenital corneal opacities. He is a twin who was born prematurely with multiple health needs. Early intervention services just started recently due to an extended stay in the NICU. Helen works in conjunction with an Arizona Early Intervention Program team that includes a vision specialist, occupational therapist, and physical therapist.

When asked about her hopes for the future regarding educational services for children and youth who are deafblind, Helen said that she would like to see the provision of interveners be a standard consideration instead of a matter of contention with education agencies.

Every child with deafblindness is a unique individual who deserves access to their environment. Observe, observe, observe to learn their strengths and areas of need, building trust through gentle, inviting interaction. And remember the mantra "do with, not for."

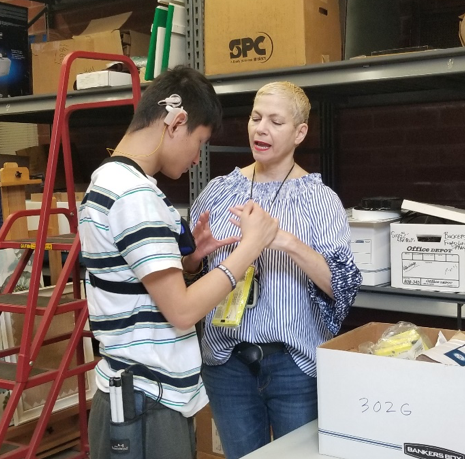

Linda Bernett - California

Published March 2021

Linda Bernett’s journey to understanding deaf-blindness began when a retiring colleague asked her to take over work with a student who was deaf-blind. Now, ten years later, Linda is still working with that student, helping him prepare to graduate and transition to adult life.

To learn all she could about deaf-blindness, Linda reached out for guidance, training, and support from many organizations, especially California Deafblind Services (CDBS), which provided a number of instructional and collaborative consultations. She also attended workshops on deaf-blindness and accessed resources and strategies on the CDBS website and NCDB’s Open Hands, Open Access: Deaf-Blind Intervener Learning Modules.

In her current role as an itinerant teacher of students who are Deaf and hard of hearing with the Los Angeles Unified School District, Linda is working with preschoolers with deaf-blindness. “It’s teaching me a lot about the crucial nature of early intervention,” she explains. “What non-disabled children learn incidentally from the moment they are born, we must create for our kids with deaf-blindness.”

“The world can be a scary place for children with deaf-blindness, and it is our job to make them feel safe so they are relieved of anxiety and open to learning,” Linda says. She advises teachers to be patient, move at the child's pace, and collaborate with other team members to give students structure, consistency, and repetition. She adds, “Kids with deaf-blindness are happier when they are engaged in activities, part of a community, and respected as valued members of society.”

Students with deaf-blindness really benefit when teachers receive the specialized training needed to work with this population. This helps maximize the student’s skills, so that they, these individuals who are people's sons and daughters and our neighbors, have opportunities to be their best selves as members of our communities and workplaces.

Madilynn Sipe - California

Published May 2021

As an education specialist in visual impairment with a clinical rehabilitative services credential in orientation and mobility (O&M), Madilynn Sipe’s caseload has included students with deafblindness ranging from preschool to high school age in both general education and special education classroom settings. Today, she works for the Contra Costa County Office of Education as a teacher of the visually impaired and an O&M specialist and is currently working with a high school student with CHARGE syndrome.

Prior to the pandemic, Madilynn was collaborating with a deaf and hard of hearing specialist and an intervener to help the student learn travel routes around the school. For example, for one route the student would go to the school’s library and check out a book that had braille and tactile graphics.

Madilynn says she was fortunate to receive training at the Helen Keller National Center, where she underwent a number of simulated deafblind experiences, including navigating intersections and using a variety of assistive technologies. She also credits NCDB’s Open Hands, Open Access: Deaf-Blind Intervener Learning Modules, and workshops on active learning, for enhancing her understanding of deafblindness and instructional strategies.

The technical assistance Madilynn received from California Deafblind Services (CDBS) has been particularly helpful. “They provided in-services for our IEP teams that were tailored to each student on my caseload who needed specific support strategies,” she explains.

Madilynn recommends that those who work with students with deafblindness really get to know them and find out their interests and motivations. “This information can help you as well as the parent and other IEP team members collaborate to provide meaningful instruction,” she says. “Some IEP teams might have five or more specialists, but if those specialists do not collaborate on their communication approach and activities, it can be very confusing for the student.”

Ongoing training for educators and school staff should become standard practice so there’s a greater awareness and understanding of deafblindness. This will help us all be more proactive regarding accessibility within schools and in the community.

Julia Bowman - Illinois

Published January 2021

Julia Bowman is a teacher of the visually impaired with an early intervention credential. She first became interested in working with children with deafblindness when she was part of a parent group for caregivers of babies with visual impairments. One of the infants in the group was deafblind, and Julia and the baby’s mom became fast friends. Today she works for the Illinois School for the Visually Impaired as a birth to three educator, developmental therapist for vision, and teacher.

Julia’s training in deafblind education involved completing NCDB’s Open Hands, Open Access: Deaf-Blind Intervener Learning Modules, as well as online courses on using active learning techniques. She is currently working with a one-year-old who has hearing loss and visual impairment. Because the child’s vision issues resemble cortical visual impairment (CVI), Julia decided to use visual support strategies and active learning to encourage the child’s curiosity and interest in reaching for objects—for example, by using stay-put learning environments, and color to highlight particular objects. Julia says the child has responded very well to these strategies and that “she now explores objects independently and is becoming mobile.”

Julia emphasizes collaboration when working with a child who is deaf-blind. Her advice for new teachers is to focus on teamwork and “talk to your colleagues!” For example, she always connects with the hearing specialist on the educational team and tries to co-treat as often as possible. Likewise, she consults with her colleagues at Project Reach: Illinois Deafblind Services whenever she has a student with deafblindness on her caseload.

Educational strategies for students with deafblindness benefit students with many different disabilities. I wish that more special education teachers were aware of them.

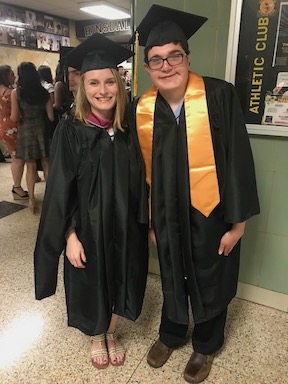

Emily Britz - Illinois

Published February 2021

Emily Britz began her career as a teacher of the visually impaired at a life skills program, working with numerous students with deafblindness. There, she partnered with an intervener and teacher of the deaf to create tactile communication systems, picture systems, anticipation charts, and routines for her students. The experience inspired her to receive certification as an intervener from Utah State University’s Deafblind Intervener Training program.

“The intervener training was amazing!” she says. “In college I didn’t get a lot of information on deaf-blindness because the population is so small, but when I got started working in special education, I had quite a few children with deaf-blindness on my caseload.” She says the intervener training gave her a much better understanding of how dual sensory loss impacts learning.

Today, Emily works at the Belleville Area Special Education Services Cooperative, which serves 23 member school districts in Illinois. She emphasizes the importance of creating routines for her students with deaf-blindness. “We build routines for everything, and it is amazing to see how kids that are non-verbal are learning, anticipating, and communicating.”

In the future, Emily hopes there will be more opportunities for training in and awareness of deafblindness, especially for interveners. “The word ‘intervener’ can be intimidating for some, especially during the IEP process,” she explains. “It would be nice to see more interveners available for students who can benefit from their services.”

Working with a variety of kids who are deafblind has been a pure joy in my life. I love how it challenges me to think outside the box. There's nothing better than when I am able to witness them accomplish a goal!

Sara Edwards - Illinois

Published February 2021

Sara Edwards witnessed first-hand the impact early intervention can have on a child with a sensory impairment by seeing how much a developmental therapist for vision (DT/V) supported her own children’s learning. Both were born visually impaired. The DT/V’s work inspired Sara to become a teacher of the visually impaired, a DT/V, and work in early intervention. Today, she is an educator at Illinois School for the Visually Impaired, where her caseload includes children with differing levels of vision loss, some with additional disabilities, including students who are deaf-blind.

“After working with my first child who was deaf-blind,” says Sara, “I quickly realized the lack of information and training I had, and I lacked resources to share with the families. I really had to do my research.” Sara explains that most of what she now knows about deaf-blindness has come from hands-on classroom experience, the Open Hands, Open Access: Deaf-Blind Intervener Learning Modules, and from multiple training programs and conferences. She also frequently connects with colleagues at Project Reach, the Illinois state deaf-blind project, for resources and information.

Sara currently works with two students who are deaf-blind, often co-treating with a developmental therapist for hearing in early intervention. “I enjoy incorporating activities that promote the use of all functioning senses so that they can learn, play, and explore their environments independently,” she says.

Every child is unique! Take the time to observe the child and learn what they like and don't like. Take that information to create individualized lessons that will keep the child engaged in a variety of activities. We want our students to be active learners!

Susan Hamlink - Illinois

Published January 2021

Susan Hamlink began her path to working with students who are deaf-blind after tutoring Deaf students as a teenager. She began her career as an itinerant teacher of students who are Deaf and hard of hearing (TODHH) and went on to receive a master’s in rehabilitation counseling. Her introduction to deaf-blindness was when she briefly worked as a case manager for individuals with deaf-blindness.

Today she is in her eleventh year of teaching at Philip J. Rock Center and School, a residential school for students with deaf-blindness, and is licensed as a TODHH, a learning behavioral specialist I, a learning behavioral specialist II (transition specialist), and in elementary education. She credits NCDB’s Open Hands, Open Access: Deaf-Blind Intervener Learning Modules, her state’s deaf-blind project (Project Reach), and haptic training for increasing her knowledge and skills for working with students who are deaf-blind.

Susan currently works with four students with deaf-blindness who have vastly different abilities and needs. For example, one is totally blind and uses a hearing aid; another has no hearing and limited useful vision. Their different needs greatly influence how they learn and access information. “For example,” she says, “when I read a story, I show pictures to one and to the other I use objects.” Although this process can make instruction more challenging, she explains, “I know that the way I present information impacts how much my students are able to access.”

Every child with deaf-blindness is so different. Just because you have experience, it doesn’t mean that you are not always learning new things. Students all learn at different rates. Have patience.

Morgan Hendon - Illinois

Published January 2021

One of the things Morgan Hendon loves most about her job is that “students push me each week to become creative in planning lessons to meet their needs.” As a teacher for students with visual impairments and a certified orientation and mobility specialist, Morgan currently works with three students who have deaf-blindness at Park School in Evanston, a therapeutic public day school. Each student has different communication, sensory, and accommodation/modification needs.

Morgan has received training and support from her state’s deaf-blind project (Project Reach) and takes classes from the University of South Dakota on deaf-blindness. Likewise, while at Park School, she learned basic sign language, a skill she strongly advises for teachers who work with students who are deaf-blind. Morgan also recommends that teachers lean on their colleagues for support. “It’s imperative for us to be flexible and help each other recognize what is working and what isn't,” she explains. “It's okay for things not to go as planned as this is what pushes us as teachers!”

She says she is “continually amazed at how smart and hard working my students with deaf-blindness are and how dedicated their parents are to ensuring they reach their education and life goals.” She hopes in the future there will be greater awareness of the many educational services and supports available to this important population of students.

Teachers working with students with deaf-blindness should invest in professional development centered on deaf-blindness. When I first began teaching, I had only read about students with deaf-blindness. It is a very different situation when you are creating and implementing an educational program.

Jennifer Hoffmann - Illinois

Published August 2021

Jennifer Hoffmann is a teacher of the visually impaired at Waukegan Public Schools in Illinois. She currently works with a medically-complex 3-year-old who is deaf-blind, helping him transition from home to school.

Jennifer worked to assure the family their child would be safe and well cared for. And, because she had previously developed a relationship with them during early intervention, she was able to facilitate communication between the educational team members and family.

In addition to her work experiences as a TVI and developmental therapist for vision (DT/V), Jennifer has completed courses in the Concentration in Deaf-Blindness and High Intensity Support Needs offered by the University of South Dakota. Among other topics, the courses focused on communication strategies for working with students with deaf-blindness as well as assessment and instructional practices.

From her training and work experience, Jennifer believes that those working with students who are deaf-blind should “slow down, follow the student's lead, find ways to play and laugh, and use strategies that will enhance their learning.” Importantly, she adds, “it’s okay to ask for help. Because deaf-blindness is so unique, learning about best practices is ongoing.”

My hopes are that more educators participate in training that’s specifically focused on the best practices, needs, and strategies for working with children who are deaf-blind and that we put those practices into action.

Rebecca Peary - Illinois

Published February 2021

After receiving certification as a Teacher of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (TODHH), Rebecca Peary was often placed in classrooms with DHH students who had additional needs, such as vision loss. “I love working with these unique students,” she says, “and the challenges and successes they present.”

To learn more about deaf-blindness, Rebecca has engaged in self-study and attended professional development courses, including some offered by Project Reach: Illinois Deafblind Services. She also emphasizes the importance of on-the-job and hands-on personal experiences with students and their families.

As a DHH teacher at Hinsdale South High School, Rebecca currently teaches three students who are deaf and have significant vision needs. They all use sign language as their main mode of communication along with picture supports. “Because their communication needs are greatly visual,” she explains, “it is imperative that their communication partners sign within each student’s ‘box of vision,’ and use simple, enlarged pictures. It’s also important that they practice patience.”

Rebecca says that over the years, she has seen excellent gains in accessibility for DHH students and students with deaf-blindness, but there are still challenges and lots of room for improvement. In particular, she hopes that accessibility will become natural in all environments, both inside and outside of the classroom.

When working with a student who has deaf-blindness, it’s important to think outside the box and try to look at the world from the student’s perspective.

Wendy Buckley - Massachusetts

Published June 2021

Wendy Buckley entered the field of deafblindness quite by chance when she applied for a position at Perkins School for the Blind and was hired to work in one of the school’s cottages with two young boys who were deafblind due to Congenital Rubella Syndrome. The boys were attending Perkins’ residential program when Wendy applied in 1976. The experience sparked her interest in learning more about language and communication development, and ultimately led to a career working with children with deafblindness.

Wendy received a master’s degree as a Teacher of Students with Severe and Multiple Disabilities, with a Specialization in Deafblindness, from Boston College. She also attended numerous training programs on deafblindness. She credits her on-the-job experience at Perkins for improving her teaching and understanding of dual sensory impairment. “I have learned so much from the students themselves!” she says.

Today, Wendy works with a range of students in Perkins’ Deafblind Program through her dual role as an assistive technology specialist and braille teacher. “I have the unique opportunity to work with both specialized technology tools, such as eye gaze, with young children working on early vision, and to focus on early literacy by teaching braille to others,” she explains.

Wendy urges those who work with children who are deafblind to develop a relationship and build mutual trust. She also recommends being a good observer. “Communication takes many forms, and it is happening all around you,” she says. “When you take time to observe and are responsive to your students’ actions, you will have wonderful conversations!”

I dream of an educational world where all children with deafblindness can be recognized for their strengths, be acknowledged for their uniqueness, and be celebrated for their successes.

Pam Young - Nevada

Published February 2021

Pam Young had been working with children with disabilities at Nevada Early Intervention Services (NEIS) when she attended the 2009 Western Regional Early Intervention Conference. That, she says, was the beginning of true love. “I found my home with children who have sensory disabilities, including deaf-blindness, and have never looked back.”

She took advantage of a host of training opportunities to learn more about deaf-blindness, including a course on understanding deaf-blindness from the SKI-HI Institute through the Nevada deaf-blind project and training as a parent coach for children who are deaf/ hard-of-hearing. She received a teacher of the visually impaired endorsement from Portland State University and a CVI endorsement from Perkins School for the Blind.

Pam is now a developmental specialist and teacher of students with visual impairments at NEIS. She currently has two students with deaf-blindness: a medically-fragile child who has limited motion and use of the hands and another who has multiple challenging disabilities but is more mobile. The first responds well to soft voices and likes being held while the second is highly verbal and a bit headstrong. Not surprisingly, Pam works hard to make modifications in the learning environment to take advantage of each child’s unique challenges and abilities.

“I think the biggest thing I have learned about working with children who are deaf-blind is to see them as children first,” she explains. “Just like all children, they learn best through play.” One of her favorite things to do is to make or adapt toys, such as PVC pipe toy hangers, that allow a child to play independently.

My hope is for broader educational opportunities for children who are deaf-blind, including increased training in deaf-blindness for teachers and additional funding for services and equipment for this special population.

Sarah Keyes - New York

Published January 2021

Sarah Keyes, an itinerant teacher of the deaf in New York, became interested in deaf-blindness after having a number of children on her caseload who were deaf-blind. She has received training in deaf-blindness from the New York Deaf-Blind Collaborative (New York’s state deaf-blind project) and credits staff there with teaching her how to build trust with students and help them develop communication skills.

One of Sarah’s current students is a 12-year-old girl she has worked with since age 3. The student has cortical visual impairment and wears bilateral cochlear implants. She also has developmental delays and extensive medical concerns. Sarah says that to watch this student grow as a person and communicator has been amazing. “To see how strong and resilient she is,” says Sarah, “and how no matter what is happening she tries to communicate with us, has made such an impact on me as a teacher. As she grows and changes, so does her program to fit her communication style and personal needs.”

Her advice to other teachers about working with children who are deaf-blind is to work as a team, have open discussions, be patient, see things from the student’s perspective, and respect each one as a unique individual. These are the keys to success when working with students who are deaf-blind.

Opening the world for our students requires staff and families to be open minded about how to help them learn about the world in their own way. My most important training comes from my students—they let me know what works and what does not.

Iryna Shkarbanov – North Carolina

Published May 2021

As a mother of a child with hearing loss, Iryna Shkarbanov says her personal experience helps her better understand the unique educational, social, and emotional needs of her students with deaf-blindness. “It makes me an even greater advocate for my students and their success at school,” she says.

Iryna is a special education teacher at North Ridge Elementary in Wake County, working with students with dual sensory impairments in both general and special education settings. Most students have significant support needs and communicate using a variety of methods, including tactile sign language, objects, spoken language, pictures, and 3D symbols.

She enjoys the creative aspects of the job, such as modifying and adapting materials for lesson plans, individual schedules, and activities so they fit each student's academic needs. “My favorite part of the job is finding ways to engage students in activities and learning and helping them connect with their peers and teachers throughout the school day,” she explains.

Iryna received a degree in Adapted Curriculum Teaching from William Peace University and is working on a master’s in Special Education with a concentration in Deaf/Hard of Hearing (DHH) Education from Minot State University. Over the years, she has attended numerous webinars and training programs on deaf-blindness. She’s also completed 56 hours of practicum training in applying the principles of listening and spoken language therapy from the Children's Cochlear Implant Center at the University of North Carolina.

Iryna says that her students' biggest challenge is building relationships with their teachers and peers. “My team and I put a lot of effort into building a trusting relationship with students before introducing new concepts or changes in their school environment,” she explains.

A child with deaf-blindness needs to feel physically and emotionally safe, to have close, supportive relationships with teachers and school staff, and to believe that they are capable and able to learn. These fundamental needs are all prerequisites for their success.

Lacey Long - North Dakota

Published April 2021

Over the years, Lacey Long has provided orientation and mobility services to students with deaf-blindness and as well as homebound services for a medically fragile preschooler with CVI and hearing loss. But she has built a very special relationship with a student who has Usher Syndrome Type 1, a disease in which children are typically born deaf and experience progressive vision loss. Lacey has worked closely with the student, who’s now a 7th-grader, since she was in kindergarten. “We tackle every obstacle with her progressive condition together,” she says.

Lacey has received a number of certifications that enable her to work effectively with students who are deafblind. She is a teacher of the visually impaired (TVI), a teacher of the Deaf (TOD), and a Certified Orientation and Mobility Specialist (COMS). She interned at the Helen Keller National Center to become a Certified Assistive Technology Instruction Specialist (CATIS) for people with visual impairments. Her professional development efforts have also included completing all 27 of NCDB’s Open Hands, Open Access: Deaf-Blind Intervener Learning Modules (OHOA).

Currently Lacey works for the Morton-Sioux Special Education Unit in North Dakota as a TVI/TOD/COMS/CATIS. She also collaborates with staff at the North Dakota Dual Sensory Project to moderate the OHOA modules for credit through Minot State University.

Because the number of students on the deafblind census in North Dakota and other small states is extremely low, Lacey believes it is critical to have well-trained, knowledgeable professionals. She credits programs like the North Dakota Summer Institute with helping to increase educational services and supports for students who are deafblind. “I would love to see institutes like this continue to increase,” she says.

If I learned anything from the OHOA modules and my time at HKNC, it’s the importance of touch in working with students who are deafblind. I always try to incorporate use of touch and tactile awareness activities in my lessons, along with the other senses.

Sharon Jones - South Dakota

Published February 2021

As a Child of Deaf Adults, Sharon Jones understood deafness on a deeply personal level. While working as an educational interpreter, a student with deaf-blindness was added to her caseload, and she knew right away that she needed to learn more about deaf-blindness. “For me,” she says, “deafness is a very navigable sensory loss, but combining both losses was not in my comfort zone at all!”

Through the South Dakota State Deaf-Blind Project, Sharon started her training by taking NCDB’s Open Hands, Open Access Deaf-Blind Intervener Learning Modules and attending conferences related to deaf-blindness. The training helped her work more effectively with her student.

Now, Sharon is a teacher of students who are Deaf (TOD) and works as an outreach consultant for the South Dakota School for the Deaf. She continues adding to her knowledge through independent reading on subjects such as language development in children with deaf-blindness.

Sharon is currently working with her first infant who is deaf-blind. She says her training has been a huge asset, particularly in her early intervention work with the family. She explains, “His mother is fantastic! She is learning to use touch and object cues and, because we don’t yet know his hearing status, I’ve encouraged her to talk to him all the time.”

Sharon believes that many TODs and teachers of students with visual impairments have a gap in knowledge about deaf-blindness. “Each group focuses more on the students who are typical in their field,” she says, “but students with deaf-blindness need to be explicitly taught in a much different way than if they had hearing or vision loss alone.”

I hope that practitioners recognize how important it is to learn more about deaf-blindness before they have that first student with deaf-blindness who needs them to fully understand their unique dual sensory loss.

Jennifer Magee - Texas

Published March 2021

Jennifer Magee has been teaching students who are deafblind for 13 years. Her interest in deafblindness increased when she worked with a 3-year-old with deaf-blindness and did not know where to start. She quickly realized that “the best practices for students who are deaf and hard of hearing and students with additional disabilities are not always appropriate for students who are deafblind.”

Since then, Jennifer has had extensive training and mentorships in deafblindness, for example, through the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired (TSBVI) and their Outreach team. She is currently in her second year of the Teachers of Students who are Deafblind (TDB) Pilot Program at TSBVI and is just completing her last semester at Texas Tech University to become a certified TDB.

Until recently, Jennifer was an itinerant teacher in Texas, with seven students with deafblindness on her caseload. Beginning in February 2021, she took on an administrative role in which she will train a variety of teachers, other service providers, and administrators to provide services for students who are deafblind. Working together, she says, “we can transform the programming of students with deafblindness through data from authentic assessment, meaningful goals and objectives, and appropriate accommodations.”

Jennifer believes teachers of the deafblind and others who work with sensory loss have “the most challenging and exhausting yet rewarding jobs in education!” She adds that “through collaboration with the educational team, including the parents and assistance from specialists, we have the opportunity to change lives by creating meaning, purpose, and joy for students and their families.”

I hope more states will recognize the need for interveners and TDBs, and that teachers of the visually impaired and the deaf and hard of hearing as well as certified orientation and mobility specialists recognize the need for additional training and expertise in deafblindness.

Crystal Sapir - Texas

Published April 2021

Crystal Sapir’s first experience with DeafBlindness happened when she was teaching at a school for children with autism that had a day program for DeafBlind adults. This inspired her to learn sign language, a skill she later put to use in a public school, where she had students with DeafBlindness in her own classroom.

Working closely with a DeafBlind specialist and a teacher of the visually impaired (TVI), she learned how to use calendar systems, build routines, make experience books, and modify the curriculum to meet individual student needs. Crystal says she was lucky to be mentored by these experts when she first began working with students with DeafBlindness. “I gained so much from their knowledge and experience. Having them in my classroom hands-on really helped me integrate tools and materials to help build communication with my students. I would have not known any of these skills had they not invested so much time in me and the students!”

Crystal credits the DeafBlind specialist and TVI for encouraging her to pursue higher education. She has completed the Visual Impairment Program and Deafblind Graduate Certificate program at Texas Tech University and taken advantage of training opportunities from a number of other agencies. She is also a certified teacher of students who are Deaf and hard of hearing, an early intervention specialist, and is currently enrolled in the Teacher of Students who are Deafblind Pilot Program through the Texas Deafblind Project.

In her current position as a teacher of students who are Deaf and hard of hearing and DeafBlind for the Dallas Independent School District, Crystal has several students with DeafBlindness who are in the developmental stages of learning language. She says she especially enjoys watching their shared communication when they begin to understand each other.

In the future, Crystal hopes districts will hire qualified interveners and provide training for them as well as classroom teachers in DeafBlindness. “Students deserve proficient language models when acquiring language,” she says.

If you have a student with DeafBlindness in your classroom, work to build a relationship with the student, take your time, and let them discover how to communicate with you.

Stacie Terhark – Texas

Published March 2021

Stacie Terhark was a graduate student at Vanderbilt University when she volunteered to work with the Tennessee Deaf-Blind Project. “I fell in love with this fascinating population of students,” she says, “and haven’t looked back since!”

Stacie went on to receive a master’s in deaf education and took several courses on deaf-blindness and deaf-blind education. She is currently completing coursework for a graduate certificate in deaf-blindness through Texas Tech University and is participating in the Teacher of Students who are Deafblind Pilot Program through the Texas Deafblind Project/Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired Outreach Program.

In her position as an Itinerant Teacher of the Deaf-Blind for the Houston Independent School District, Stacie works with more than 20 students who are deaf-blind from birth to 22 years old. Because each student has unique needs and varying degrees of visual impairment and hearing loss, she explains, “I am constantly learning and growing in my knowledge about deaf-blindness and best practices.”

Stacie acknowledges that it can sometimes be discouraging when students who are deaf-blind don’t progress at the same rate as their hearing and sighted peers. Nevertheless, she recommends that teachers “have patience, and with time and consistency, each student will grow and blossom in their own way.”

She recommends that all members of the educational team, including administrators, therapists, and general and special education teachers, develop a greater awareness of the needs of students with deaf-blindness.

My hopes are that we continue to have opportunities for professional education in deaf-blindness and that more intervener positions are created in school systems across the nation